Regarding the Russian-Ukrainian war, Western narratives emphasize Russia’s aggression, but a deeper geopolitical approach can offer other explanations. Here are some.

In order to support their political aspirations, countries that define themselves as democracies need some sort of explanation for their voters. These are usually narratives based on axioms, accepted preconditions that do not require proof and logically lead to the support of the desired politics if the preconditions are not questioned by anyone.

One of the best examples of this in Europe is the position taken on the Russian-Ukrainian war, which fundamentally shapes the future of the continent. In mainstream Western media, the cause of the conflict is Russia, or rather, Vladimir Putin’s aggressive expansionist policy, which aims to restore the former Soviet Union and poses a direct threat to Western Europe. One of the most recent manifestations of this concept was a study titled Europe Alone published in the summer edition of Foreign Policy magazine, which summarizes the thoughts of nine politicians and opinion leaders on the war. Its essence is that

Moscow started the first major land war in Europe since World War II with the aim of restoring its Cold War empire.

What are the underlying causes, motives?

However, the continent’s worldview explaining the situation can change significantly if we do not start the story with the idea that Russia attacked Ukraine for no reason, but with the negotiations that ended the Cold War, and with broader geopolitical perspectives, based on geopolitical theories developed over a hundred years ago that explain current conflicts well.

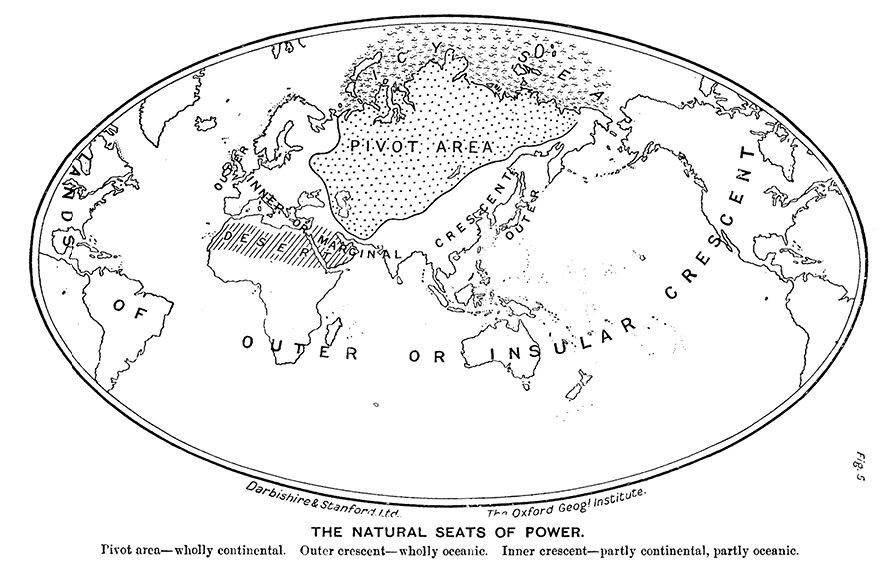

In this regard, fundamental importance is attached to the theory of Scottish-born university professor Halford Mackinder, who divided the globe into a hierarchical system of concentric circles. At the center is the “geographical axis of history,” with the Heartland at its center, a region stretching from the Volga to the Yangtze and from the Himalayas to the Arctic. The outer ring, the “Crescent of Islands” (outer crescent), includes America, England, and Australia. Between the two regions lies the “inner or marginal crescent” (Rimland). Mackinder assigned strategic priority to the “geographical axis of history,” in his famous, oft-quoted formulation:

Whoever controls Eastern Europe controls the Heartland, who controls the Heartland, controls the World-Island, who controls the World-Island, controls the world.”

He believed that the main task of Anglo-Saxon geopolitics was to prevent the formation of a strategic continental alliance along the “geographical axis of history.” Therefore, the strategy of the forces of the “Crescent of Islands” should be to cut off as many coastal areas from the Heartland as possible and place them under the influence of the “island civilization.”

Figure 1: Representation of the Mackinder worldview on a map.

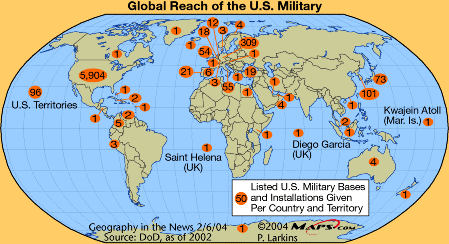

Alfred Mahan (1840–1914), the American admiral of the navy, provided a concrete way to implement Mackinder’s idea globally by extending the “anaconda principle” used in the American Civil War, namely, that

land powers like Germany, Russia, or China should be surrounded from the seas and ideally cut off from access to coastal areas.

If we look at the map of American military bases today, we can see that this principle was implemented after World War II.

Figure 2: Military bases of the United States and NATO. Source: The History Reader.

American Nicholas Spykman (1893–1943) theoretically supported Mahan’s proposal and reversed Mackinder’s original proposition, saying that “whoever controls the Rimland, controls Eurasia, who controls Eurasia, controls the fate of the world.”

English, German, or Russian foundations?

Opposed to Anglo-Saxon geopolitical theories is the theory of German Karl Haushofer (1869–1946), which expresses the interests of continental Europe and primarily Germany within it. According to him, Germany is the spatial and cultural center of Europe, and the country was made the natural adversary of the Western maritime powers – England, France, and prospectively the United States. In such a situation, Germany could not count on a strong alliance with the powers of the “Crescent of Islands,” and he believed it was necessary to create a continental bloc, a Berlin-Moscow-Tokyo axis.

Today, Russian geopolitical interests are represented by Alexander Dugin (1962–), who believes that there is a fundamental antagonistic conflict between the globalist elite he calls mondialists and the forces that adhere to national sovereignty. At the helm of the mondialist world community is the cosmopolitan elite, which seeks to rule not over societies, but over masses of individuals.

Russia, adhering to traditional values, stands opposed to mondialists, and its mission – as it extends over two continents – is the economic integration of the Eurasian region, a political direction known as Eurasianism.

The most renowned theoretician of American geopolitical interests after the Cold War is Zbigniew Brzezinski (1928–2017), a Polish-born geostrategist. In his most frequently cited work, “The Grand Chessboard” published in 1997, he deals primarily with the geopolitical changes after the dissolution of the Soviet Union and essentially states that Russia is no longer an equal partner to the West, and must either submit to the world order defined by Western powers, or confront it and face isolation. Brzezinski believes that Ukraine is part of the West, but without Ukraine, Russia is no longer a great power, but a dominantly Asian imperial state, which must be treated accordingly.

The political guiding line

Taking into account the various geopolitical theories expressing the interests of great powers, a completely different picture of the Russian-Ukrainian war can emerge than what is suggested by mainstream Western media. It becomes clear that

this is not Putin’s war against sovereign Ukraine, but a geopolitical rearrangement where Ukraine has ended up on the front line.

Even more so when, after the geopolitical theories, we consider the political events that followed.

Mikhail Gorbachev, elected General Secretary of the Soviet Union in 1985, wanted to modernize his country and improve relations with the West. This led to negotiations on the reunification of Germany and, within that, Germany’s NATO membership, during which US Secretary of State James Baker promised that if a unified Germany could remain a NATO member, NATO would not expand eastward even by a centimeter.1

Despite the promises made to Gorbachev, NATO’s eastern expansion began almost immediately. In 1993, the Partnership for Peace Program was established, which in practice was a prelude to NATO membership, and by 1994, all former socialist countries and the majority of the member states of the dissolved Soviet Union became “partners for peace.” In 1997, Poland, the Czech Republic, and Hungary were invited to accession talks, and in 1999, they became NATO members.

The Russians increasingly protested against the expansion, so Brzezinski suggested that NATO declare that any state meeting the necessary criteria could be a member of the organization, including Russia. He believed that this would put an end to debates about NATO expansion, while Russia would not have the right to veto the membership of new members of the organization.

The NATO expansion was thus decided in the early 1990s, but it was only brought up for debate in the Foreign Relations Committee of the US Senate in late 1997. Those arguing in favor of extending the organization to Central Europe, such as the current US President Joe Biden or the then Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, essentially said that with the withdrawal of Soviet troops, there was a power vacuum that someone would fill, and it would be best for this to be NATO.

However, several senators and external experts questioned this idea and took a stand against the military alliance’s expansion, pointing out that

with NATO expanding, Russia was being isolated at a time when the United States’ main rival was shifting to China.

The strongest criticism, however, came from George F. Kennan, the former chief ideologist of the Cold War, who, in an article published in The New York Times in February 1997, called the expansion a fatal mistake. Nevertheless, the Senate overwhelmingly supported NATO’s expansion.

The next crucial step for the Ukrainian war was in 2008 at the NATO summit in Bucharest, where, despite protests from the six founding members of the European Economic Community, as well as Greece, Norway, and Hungary, Ukraine’s membership was prospectively put forward under pressure from the USA, Great Britain, the Baltic states, and Poland.

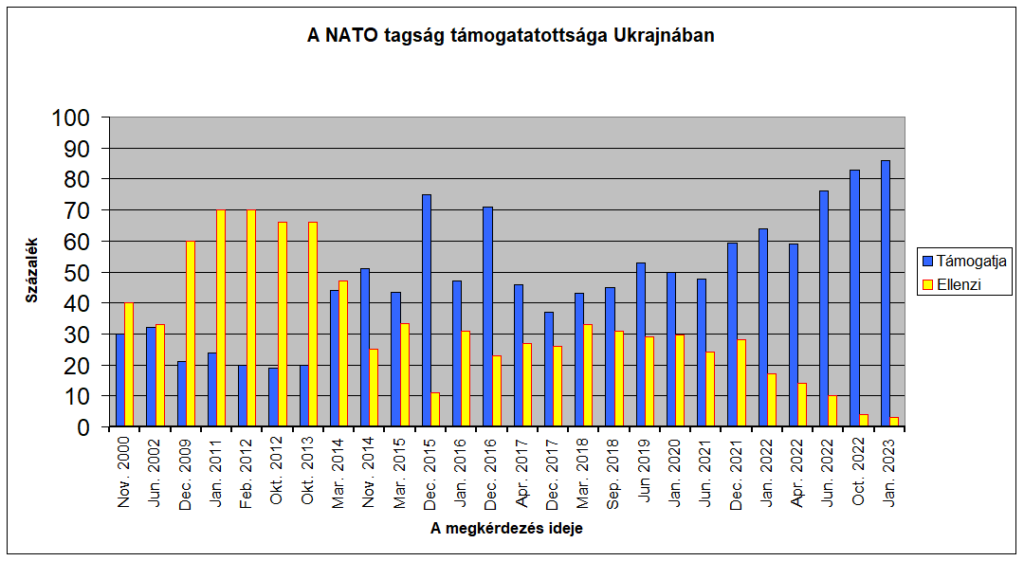

Initially, the Ukrainians rejected the accession by a significant two-thirds majority, and several politicians, such as Leonid Kuchma, Ukraine’s second elected president in 1994 and Viktor Yanukovych, who was elected president in 2010 representing the Party of Regions, wanted to pursue a policy of neutrality seeking a balanced status between Russia and the West. This was disrupted by the “revolution” supported by the Americans (Obama administration) on the Maidan Square, which, after lengthy wrangling, led to the democratically elected president being forced to resign with the help of snipers and the formation of an extreme, nationalist, but US-serving government.

One of the new government’s first measures, supported by the US State Department, was the withdrawal of the language law recognizing the rights of linguistic minorities and the announcement of further integration with NATO.

For Russia, the loss of Sevastopol, the base of the Russian Black Sea Fleet, became a real threat, which is why it decided to annex Crimea, which never belonged to Ukraine anyway, as it was gifted by Khrushchev in 1954, in memory of the Ukrainians joining Russia 300 years earlier, fleeing Polish rule.

The government that came to power through violence, strongly anti-Russian, was not accepted by Donetsk and Luhansk, the two counties mostly inhabited by Russians, and they self-proclaimed independence. This was followed by armed clashes between government forces and the two rebel counties supported by the Russians.

Figure 3. Source: Wikipedia.

France and Germany’s leaders quickly recognized that this war was not in their interest and tried to prevent its escalation, leading to the Minsk agreements.

Russia did not have territorial demands, it simply wanted the two counties to have autonomy within Ukraine, which also served the Russian goal of preventing Ukraine’s NATO membership. However, the West did not take the Minsk agreements seriously, and as Angela Merkel later stated, their only purpose was to militarily strengthen Ukraine.

In the next seven years, military clashes between Ukrainian government forces and the two breakaway counties supported by the Russians became a constant, with Russian announcements stating that the Ukrainians shelled residential areas and caused the deaths of about 16,000 civilians.

The last negotiation between America and Russia, when the war could still have been prevented, was on January 10, 2022, in Geneva. Russia’s main request was that Ukraine not become a NATO member. However, Wendy Sherman, the US Deputy Secretary of State, firmly rejected this, stating that Washington would not allow anyone to undermine NATO’s “open-door policy,” that is, that Ukraine will eventually join the organization.

In response, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov stated that his country had no room to retreat on the matter.

This is what happened before Russia “attacked Ukraine for no reason.”

Considering the above, a completely different story unfolds than what is suggested by the West, and mainly by the mainstream media. It was not Russia expanding towards the West, but NATO – despite the promise made to Gorbachev – extending its reach to the Russian borders. Moscow continuously protested, but American politics blatantly disregarded it, treating Russia as a country defeated in the Cold War rather than an equal partner.

Ukraine’s neutrality is vital for Russia, while for America it is a meaningless sideshow because the USA’s main challenge is not Russia but China. Treating Russia as an enemy poses an economic catastrophe for Europe.

Therefore, it is completely incomprehensible why the leaders of the European Union now create war hysteria instead of upholding clear European interests as seen in 2008 (Bucharest NATO summit) and 2015 (Minsk agreements).

Our task is to present to the European public the real, documentable precedents of the war so that more people understand that this is not about a Russian threat, but about NATO overextending and a misguided, self-destructive European policy.

The article reflects the author’s opinion, which does not necessarily coincide with the editorial standpoint.